Posts Tagged ‘book reviews’

Here are the rest of the books I read in 2016-2017. There is more non-fiction, plus fiction and an explanation.

JUSTICE ISSUES

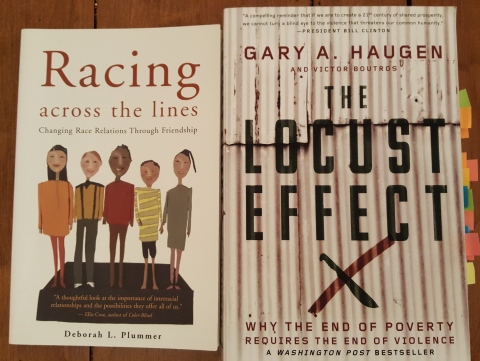

Racing Across Lines: Changing Race Relations Through Friendship by Deborah L. Plummer, Pilgrim Press, 2004, 127 pp.

Racing Across Lines: Changing Race Relations Through Friendship by Deborah L. Plummer, Pilgrim Press, 2004, 127 pp.

This is another UCC General Synod bargain that sat on my shelf for years, until it was just the right thing at the right time. The congregation I currently serve is interracial and international, bringing together people of many languages, countries and colors. I think our greatest opportunity is to build friendships across these lines. Plummer’s book explores both the promise and challenge of cross-racial socializing, boldly naming the ways that we feel most at home around those of our own race, the discomfort we feel when we are in a minority, and the ways that socializing with those of other races can help us realize our own narrow views. This is not a book about ending racism via friendship, although Plummer certainly addresses racial prejudice and white privilege in context. It is a book about friendship, and about how difficult—but worthwhile—it is to intentionally pursue friendships across racial lines.

The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence by Gary A. Haugen, Oxford University Press, 2014, 346 pp.

My congregation has a partnership with International Justice Mission, founded by Gary Haugen and engaged in justice work around the world. This book helped me understand the organization’s difficult work, the problems it addresses and the strategies it deploys. Haugen argues that criminal violence and the lack of effective law enforcement are the single biggest issues impacting impoverished people around the world. This does not mean that poor people are criminals—quite the opposite. Poverty means that you will, almost inevitably, be the victim of a crime, and the perpetrator will go unpunished. All of the aid programs for food, education, shelter and water will remain ineffective if people are not safe from violence. Haugen addresses not just oppression and state injustice, but the everyday criminal violence, police corruption and lawlessness that afflicts poor communities. IJM is doing the slow, painstaking work of building systems of justice and local law enforcement around the world, and this book describes it. What most impacted me in reading this book, however, was the realization that these same forces of corruption and the unavailability of justice to those who cannot afford to pay for it hold sway in the streets and neighborhoods of the United States, as we have especially seen in the murder of black men and women by police, with impunity.

THEOLOGY AND SPIRITUALITY

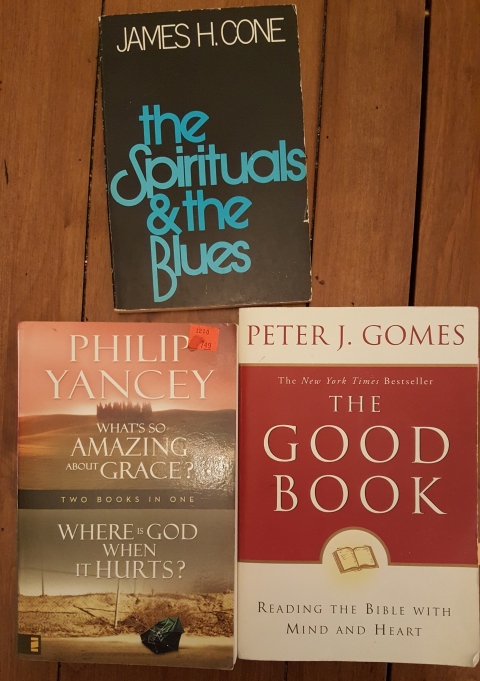

The Spirituals and the Blues by James H. Cone, Seabury Press, 1972, 152 pp.

The Spirituals and the Blues by James H. Cone, Seabury Press, 1972, 152 pp.

Another classic I finally took time to read, prompted by plans to develop a Good Friday service called “The Passion in Spirituals,” weaving together the story of the crucifixion in conversation with African-American poets and spirituals. Cone’s work gave me the appropriate theological context for understanding the spirituals, and helped me to curate the service and write the notes to accompany it. The book argues that, since many African Americans were denied access to publishing and writing, their theology and faith expression was instead passed on through the singing of spirituals. Cone then mines the spirituals and the blues for the theological insight of the black community, with special attention to the ways the lyrics claim liberation from oppression. He writes, “Resistance was the ability to create beauty and worth out of the ugliness of slave existence. … Religion is wrought out of the experience of the people who encounter the divine in the midst of historical realities.” (29) Cone’s theology, then, emerges from evidence of that religious resistance from the spirituals and the blues.

The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart by Peter J. Gomes, HarperSanFrancisco, 1996, 383 pp.

I am still questing for just the right book, one that introduces people to the Bible with an affection and a critical eye. I bought this one on that quest more than 10 years ago, and recently thought one of the chapters might adeptly address a church member’s concern. I started reading for that reason, and quickly discovered in The Good Book a 20-year-old time capsule of theological hot topics. The mid-1990s were key to my seminary and formation, and I saw all the old debates here. I was able to marvel at how far we have come, how stuck we still are, and how much farther we have moved away from Christendom and toward both cynicism and hope. Gomes’ wisdom remains solid on the topics he addresses. The chapters on “The Bible and …” (race, women, anti-semitism, homosexuality) remain of their time. It’s not that we aren’t still arguing about those topics, but the way we are talking about them has changed in the last 20 years. The remaining chapters, on more timeless topics like the good life, suffering, joy, mystery and evil, remain solid. I especially appreciated his chapter on wealth, though the income inequality and flagrant worship of opulence in our time sometimes made it seem quaint.

What’s So Amazing about Grace? and Where is God When It Hurts? by Philip Yancey, Zondervan, 1997 and 1977, respectively, published in one volume 2008, 584 pp.

Writing all these reviews in a row is proving to me how many books I have read after they have rested in waiting for many years—this two-in-one combo is another one in that category. I picked this up in surgery recovery. I think I needed some theological reflection on these questions in my own life after the tumult of the year, but I wasn’t able to handle anything too challenging. Unlike most theologians I prefer, Yancey was actually trying to answer those questions in a way that offered comfort to earnest seekers. I think I sought that solace. While Yancey’s answers did not always convince, they did offer reassurance and hope. His conversation about finding God in suffering gave practical, everyday examples of the co-existence of joy and struggle, reminding us that they often come together. More importantly, he flips the question back on Christians: “where is the church when it hurts?” (249) The book about grace, though written 20 years ago, parallels some of the conversations happening in recent books on the purpose of the church (including Glorify, Weird Church, and Standing Naked Before God, which I read this year and review in this same post). Yancey argues that grace is the thing that the church has to offer that nothing else in the world can provide. He focuses not the overwhelming nature of human sin, but on our existential need to forgive and be forgiven. He contrasts God’s desire with a world and a spirit of “ungrace,” and chastises those who act without grace toward those it deems sinners or unchristian. Both of these books were better than I expected. While there was an occasional evangelical twist I couldn’t abide, mostly they offered simple expressions of comfort to me in a difficult season. Proof that it may take me awhile, but eventually I do read these books I buy. When the moment is right, they are just what my soul needs.

ANTHROPOLOGY

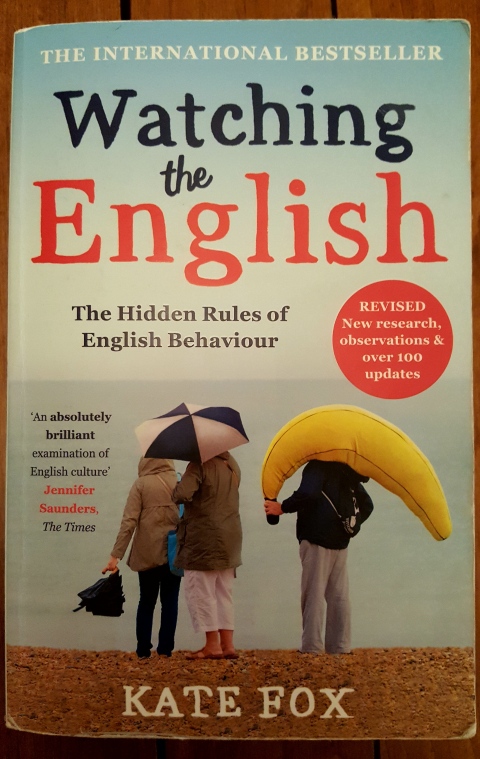

Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behavior by Kate Fox, Hodder, 2004, 583 pp.

Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behavior by Kate Fox, Hodder, 2004, 583 pp.

This was the single most helpful (and embarrassing) resource as I was getting acclimated to life in London. I am grateful to the church member who gave me her copy when I arrived. Kate Fox is an Englishwoman and an anthropologist who turned her sights on her home country, observing the behaviors, traits, cultural understandings and quirks of English people. She studies food rules, dress codes, speech patterns, rites of passage, money, taboos and every other area of culture. I read this book like a missionary studying up on a foreign culture, and realized in every single chapter something that I was doing wrong or completely misunderstanding. It was my own personal way of discovering my cultural faux pas. Fox’s writing is full of humor and self-deprecation for her home country, which is important, because she identifies self-deprecating humor as one of the most important traits of Englishness, alongside things like social awkwardness, class consciousness, and “eeyorishness.” I’m not sure I would have truly understood this book until I lived here. I’m also sure it would have taken me a lot longer to understand living here if I hadn’t had this book for help.

SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY

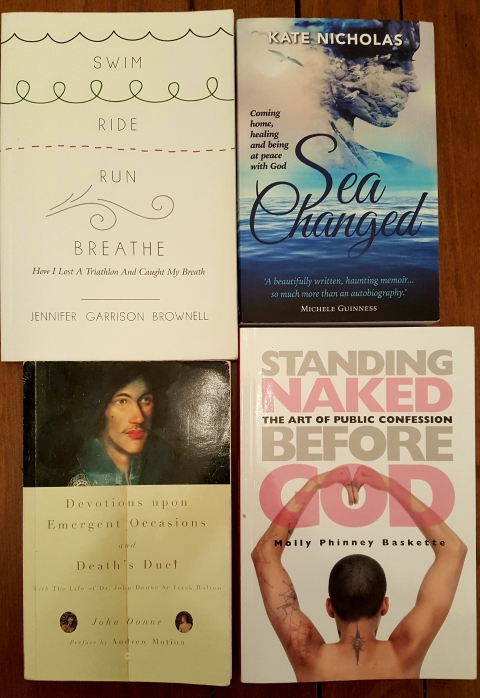

Swim, Ride, Run, Breathe: How I Lost a Triathlon and Caught My Breath by Jennifer Garrison Brownell, Pilgrim Press, 2014, 146 pp.

Swim, Ride, Run, Breathe: How I Lost a Triathlon and Caught My Breath by Jennifer Garrison Brownell, Pilgrim Press, 2014, 146 pp.

This author is a friend whose book I was delighted to read, but again it sat awhile, because it was all about timing. I read this in the thick of chemotherapy, the hardest season for me. Something about the title captured my attention—the pacing and physicality of the verbs felt like my life in the moment: “just keep going.” I didn’t have capacity to reflect, but the author did, in beautiful and powerful ways that touched my soul. The short, poignant chapters were often all I could handle. I needed to know God in the simple act of keeping moving and breathing, and this book showed the holy to me. I don’t do well with physicality, with pushing my body’s limits. This book invited me to think about the power of incarnation, and seeing the strength and courage of a fellow Jennifer encouraged me to face the hard things I was going through at the time. This is a beautiful reflection, inspirational and truth-telling, and I loved it.

Sea Changed: Coming Home, Healing and Being at Peace with God by Kate Nicholas, Authentic Media, 2016, 294 pp.

A member of my congregation introduced Kate Nicholas and I, saying “you two share cancer, preaching and a joyous spirit. I think you should connect.” That connection has been a great blessing so far, not the least of which was the introduction to this marvelous story. When she was diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer, the author started to write the story of her life to share with her two young daughters. She had had a lifetime of adventures, but the story that emerged was one of God’s presence throughout, chasing her and changing her, shaping her and transforming her life—eventually even healing her from cancer. Kate’s life story is fascinating, but especially so because she tells it with rich detail and makes the people come alive. More, though, she makes God come to life, revealing all the ways the Spirit has been quietly at work around her, calling her to faith. It is a powerful testimony and a joy to read.

Standing Naked Before God: The Art of Public Confession by Molly Phinney Baskette, Pilgrim Press, 2015, 211 pp.

This book might fit more aptly in the “church leadership” category, because the first half is a rationale and strategy for integrating public confession into the weekly worship of a congregation. As always, Molly Phinney Baskette’s writing is compelling and revealing, speaking deeply about how God is present and at work in the church’s life. But for me, again reading in the thick of treatment, it was the second half, a collection of personal confessions and testimonies, that spoke to me most deeply. They are examples of the kind of practiced, prepared confession described in the first half of the book, but they are also glimpses of individual walks with God, struggles and successes and colossal failures, all of which the Spirit redeems and transforms into messages of grace for all who listen. Each was a tiny gift of hope to me.

Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions and Death’s Duel by John Donne (with The Life of Dr. John Donne by Izaak Walton), Vintage Spiritual Classics, 1999, 234 pp.

This book spoke to me and for me in the early months of 2017. I was recovering from chemo and surgery, and turned to John Donne in similar circumstances. The “emergent occasions” which he references are the days of his deathly illness and long recovery. He prays earnestly, with faith but without consolation, for God to preserve his life through his illness, and vacillates between hope and despair as he endures treatment. When he writes about his relationship with his bed, seeing fear in the eyes of his physicians, and the pull of ministry even as he recovers, I felt such a resonance and understanding about the reality of facing a deathly illness. It was the poetry my soul needed, like the Psalmist who gives voice to our sighs. My reading was interrupted by the death of my father, and I returned to complete Death’s Duel, his final sermon as (many years after the other illness) he was preparing for his own death. Again, it offered me words and reflections that unlocked and explained my own feelings. This was an agonizing read, for the beauty and poignance were piercing for me this year.

Here is a summary of all the non-fiction books I read in 2017, sorted by category. Because there are so many, I’ll divide it into two posts. There is more non-fiction, plus fiction and an explanation.

CHURCH HISTORY

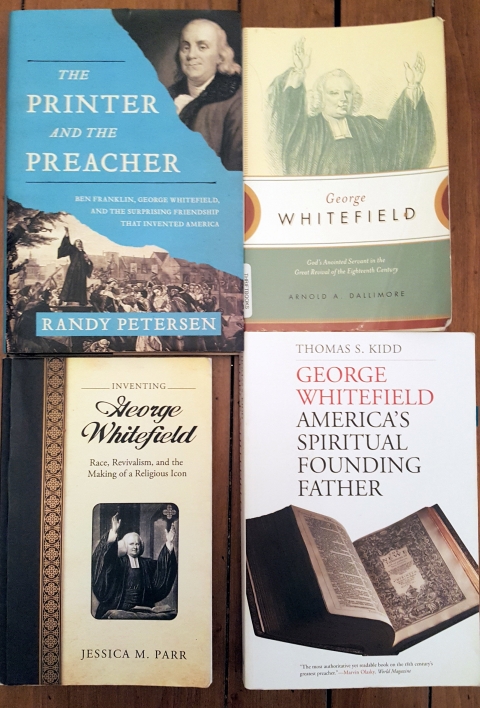

Four books about George Whitefield. One about the Reformation. Why? Studying up. The church I came to London to serve is on the site of the Whitefield Memorial Chapel, and I wanted to learn more about this great preacher who linked London and the United States in the 18th Century. Also, 2017 was the 500th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses, and I wanted to understand more about this tumultuous period of Christian history.

The Printer and the Preacher: Ben Franklin, George Whitefield and the Surprising Friendship that Invented America by Randy Petersen, Nelson Books, 2015, 281 pp.

The Printer and the Preacher: Ben Franklin, George Whitefield and the Surprising Friendship that Invented America by Randy Petersen, Nelson Books, 2015, 281 pp.

This book turned out to be terrible, but the only one of its kind. That makes it somehow still valuable, even though I don’t recommend it at all. Petersen is no scholar, and it shows on every page. His work is derivative of accredited scholars, and full of leaps and assumptions that are utterly unsupported by evidence and drawn from his own pet passions rather than helpful insight. Nevertheless, the relationship between George Whitefield and Benjamin Franklin is fascinating, and this is the only work dedicated to distilling it into a narrative. The two shared an approach to self-promotion, a concern for the well-being of the working class, and a passion for the new identity of America. I learned anecdotes and connections, even if I rolled my eyes and sifted out Petersen’s embellished interpretations.

George Whitefield: God’s Anointed Servant in the Great Revival of the Eighteenth Century, Crossway, 1990, 219 pp.

This book is a much-abbreviated summary of Dallimore’s multi-volume biography of Whitefield, as a way to make his work accessible and readable for non-scholars. Like most Whitefield biographers, Dallimore is an American evangelical whose theological perspective colors his interpretations, adds elements of moralizing and adulation I might prefer to omit, and omits more complicated or unorthodox information. However, his scholarship and storytelling are solid, and this was a helpful introductory biography for me to learn about Whitefield.

George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father by Thomas S. Kidd, Yale University Press, 2014, 325 pp.

Kidd attempts to offer the first comprehensive biography of Whitefield by a professional historian. He shares an American evangelical perspective, and this biography argues that “George Whitefield was the key figure in the first generation of Anglo-American evangelical Christianity.” (3) Kidd’s admiration of his subject, his desire to sanctify Whitefield against the Wesleys and other critics, and his whole-hearted acceptance of evangelicalism gave me pause, though the argument that Whitefield created American evangelicalism is compelling. Kidd is more comfortable than I am making peace with the hard Calvinism and racial prejudice of that movement, both then and now. This was still a helpful, comprehensive outline of Whitefield’s life, full of insights that I can draw upon and carry forward as examples for our church that carries on in his name—though with a stronger critique of those things that belong in the dust bin of history and theology.

Inventing George Whitefield: Race, Revivalism and the Making of a Religious Icon by Jessica M. Parr, University Press of Mississippi, 2015, 235 pp.

One of the most problematic aspects of Whitefield’s biography is his advocacy for the institution of slavery and its expansion into the state of Georgia. Yet his prejudices on race are not so simple, as he was also more open-minded than many in preaching the gospel to enslaved people and befriending people of African and Native American descent, believing them fully capable and worthy of Christian life. He was famously memorialized by Phillis Wheatley and praised by Olaudah Equiano. As I think about how (or whether) to reclaim Whitefield’s legacy in our ministry on his site, this is one of the most critical issues for me to understand and address. I was eager for Parr’s book to help. It did not deliver what I hoped, which was an analysis and some conclusions about his words, their repercussions and impact (positive or negative). It did at least catalog most of his interactions around race, slavery and theology, which was helpful. Instead, Parr’s book is an argument about how Whitefield and those who have since studied and written about him have tried to craft his image as a religious icon. This was itself interesting and valuable. Scholars, preachers and theologians have been able to make Whitefield over in the service to a variety of causes—and Whitefield himself not only allowed such a mutable image, but cultivated his image to be flexible and appealing to all.

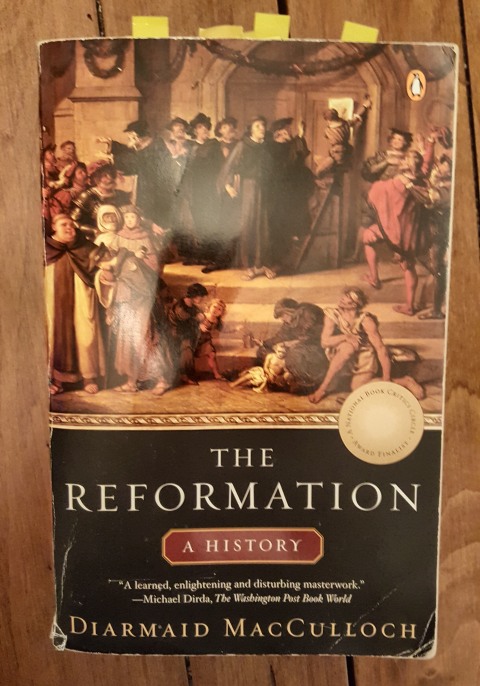

The Reformation: A History by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Penguin Books, 2003, 832 pp.

The Reformation: A History by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Penguin Books, 2003, 832 pp.

I started this book in early 2016, but couldn’t keep up in the midst of moving. It was densely packed with information, but fascinating and readable. What I appreciated most about this book was that MacCullough did not focus only on the theologians and their differences, but on the way these theological disputes were lived out in political and social realities. From the beginning, he paid attention to the everyday spiritual lives of Christians, and how the waves of Reformation impacted their relationships with God and one another. In chronicling the relationships between churches, princes and Rome, he captures the upheaval not just of war and conflict, but of spiritual homelessness found in the Reformation. A great read.

CHURCH LEADERSHIP AND PREACHING

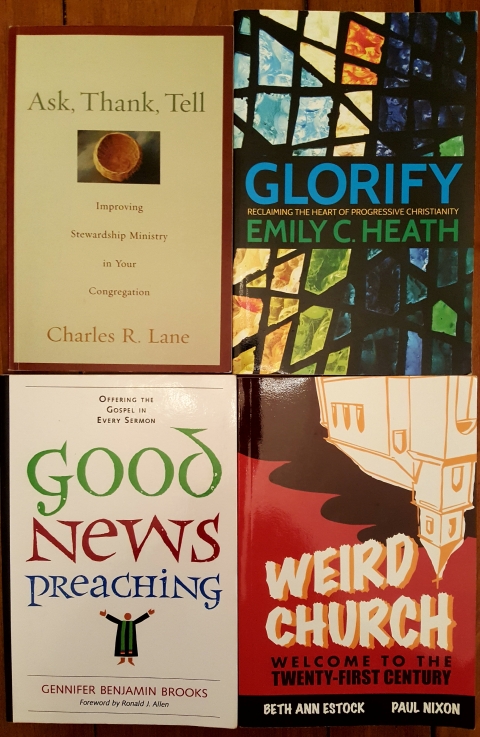

Good News Preaching: Offering the Gospel in Every Sermon by Gennifer Benjamin Brooks, Pilgrim Press, 2009, 158 pp.

Good News Preaching: Offering the Gospel in Every Sermon by Gennifer Benjamin Brooks, Pilgrim Press, 2009, 158 pp.

This book had been in my shelves for a long time, acquired on sale at some UCC General Synod, but I needed it urgently in this last year. With the Trump administration, the rise of right-wing ideologies of hate, and the impact of terrorism here in London and everywhere, it was hard not to spend every week in the pulpit condemning some new heresy and prejudice in the name of Christ. While that proclamation is also important, I recognized the need to also offer good news, hope and courage rooted in the Gospel. Brooks’ book was right on time, not only making the case for why preaching must always include good news in a bad news world, but offering techniques and examples for including this message of grace and salvation even as we sustain our prophetic critiques.

Weird Church: Welcome to the Twenty-First Century by Beth Ann Estock and Paul Nixon, Pilgrim Press, 2016, 176 pp.

Estock and Nixon are church consultants helping congregations grow, thrive and change. This book begins with an analysis of our social and ideological reality, which contains multiple worldviews at work all at once. I am not sure I agree with the evolutionary understanding Nixon and Estock offer, as though humanity is becoming more enlightened, but the worldviews they describe are readily in evidence, and in conflict, within our congregations and communities. The first half of the book identifies trends and challenges of church life today. While it was a helpful summary, there were not a wealth of ideas and insights I had not already read elsewhere. The second half of the book catalogs new incarnations of church that respond especially well to the newest worldview (not integrating the various worldviews, as we are doing in traditional settings). From dinner church to coffee house enterprises to mission outposts, they look at creative “weird” endeavors that speak to changing realities.

Ask, Thank, Tell: Improving Stewardship Ministry in Your Congregation by Charles R. Lane, Augsburg Fortress, 2006, 128 pp.

This is a popular read among clergy trying to improve their congregational giving, and it is a solid, helpful and rich resource. Lane’s main emphasis is on discipleship, and the need to develop people not as givers or members, but as disciples. Cultivating generosity is about learning to trust God with our money. I also appreciated the simple outline he offers, from the title on: ask, thank, tell. There is no life-changing program here, but too often churches try to work on better “asks” without following up on the other portions of the cycle of inspiration—thanking people for their gifts and telling them how the church’s ministry is making a difference. This is a softer, gentler approach than J. Clif Christopher’s Not Your Parents’ Offering Plate, but with similar ideas and themes.

Glorify: Reclaiming the Heart of Progressive Christianity by Emily C. Heath, Pilgrim Press, 2016, 136 pp.

This was one of my favorite books this year, and not just because Heath is a friend. This book makes the case that discipleship is the missing ingredient in progressive churches, and that we ought to be paying far more attention to the development of the faith lives of our congregations as our most critical task. Heath expresses concern that progressive Christians often define our faith by what we are against, or how we are not like “those” Christians who are anti-gay, anti-woman, anti-sex and all the rest. Instead, we should be asking how we can live lives and build communities that glorify God, with joy and compassion. That means cultivating transformed lives, letting God change us and work through us in prayer, study, generosity and—yes!—acts of justice. Heath speaks concerns and passions I have shared since seminary, and I am grateful for this clear case for the importance of discipleship in our progressive churches.

Leadership Without Easy Answers by Ronald A. Heifetz, Belknap Press, 1994, 348 pp.

Leadership Without Easy Answers by Ronald A. Heifetz, Belknap Press, 1994, 348 pp.

This book isn’t specifically about church leadership, but leadership in general. I’ve read about this book and its ideas in many sources, but it took me a long time to get around to reading the original source. In many ways, this made it feel like a refresher to concepts I already knew (and have used many times). Reading Heifetz’ arguments and defense of his ideas revealed to me how innovative he was by moving away from understanding leadership as a trait or character type and instead as an activity and skill set. Leadership doesn’t reside in personality, but in one’s ability to build trust and move people to follow. Beyond the helpful distinction between technical and adaptive change, Heifetz’ articulation of “leadership without authority” is a perfect way to capture the essence of congregational leadership, both clergy and lay. He addresses the pain and personal challenge of sustaining this kind of leadership in long-term struggles, and offers reassurance and insight. I’m glad I finally read it—now on to the next volume, Leadership on the Line, which is still on the shelf.

Here’s a summary of all the fiction I’ve read in the last 18 months, grouped by some categories and with a short review of each. Non-fiction is here and here, plus an explanation.

BEAUTIFUL AND BEST

These books are what fiction is all about—words and characters that come together to tell a powerful, moving, captivating story about being human. These brought me joy, tears and healing this year.

My Grandmother Asked Me To Tell You She’s Sorry by Frederik Backman, Washington Square Press, 2015, 372 pp.

I bought this at the airport on my way either to or from my father’s funeral. The narrator offers a child’s perspective on death and grief, on truth and fiction, on love and normality, but woven by a brilliant storyteller. Elsa’s grandmother creates for her a magical world of stories, and when she dies, Elsa journeys to discover the meaning behind them. This book spoke to my heart’s need to tell my story to make sense of my own life and its heartbreaks.

Grief is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter, Faber & Faber, 2015, 114 pp.

This book defies explanation. This short piece explores the topology of grief and loss, with all its attendant feelings, through prose-poetry in multiple voices, including the husband grieving his wife, the two sons grieving their mother, and the giant crow who comes to stay with them, who is sometimes nonsensical and sometimes the only one who makes any sense. Epic, complicated, deep and true. I want to read it again, a year later, living with new grief.

A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness, Candlewick Press, 2011, 225 pp.

Intrigued by the movie previews, I gave the book to my son for Christmas. I didn’t realize it was about a boy coming to grips with his mother’s death from cancer! And I didn’t learn it until a month later when I finally read it and talked to him about it! Not my finest parenting moment. The monster is his grief and his fear of it, and it abides with him until he opens his heart to accept the reality of loss. Another book that is deep and true, but this time for a younger audience. Even though I should have prepared my son for its content—and perhaps not given it to him right in the middle of my treatment!—it was a gift to open up conversation between us.

GOOD AND GOOD FOR YOU

These books made me feel better informed about the world and about literature, but the content was sometimes difficult and sometimes reading took work. They demand appreciation, but sometimes withhold joy.

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, Bloomsbury Press, 2011, 258 pp.

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, Bloomsbury Press, 2011, 258 pp.

This is a book about survival in the midst of poverty and hardship. As a hurricane approaches, Esch and her brothers in the Mississippi bayou work with their unreliable father to find food and shelter to survive the storm. The lives and circumstances are harsh and unrelenting, but Ward creates characters with depth and nuance. They lack much, they make choices we might disdain (dog-fighting plays a prominent role), but they have a fierce tenderness for one another that brought me to care for them. A tough but worthwhile read.

Island of Wings by Karin Altenberg, Quercus, 2011, 372 pp.

Set in 1830 on St. Kilda’s Island, the most remote corner of Britain, where a young couple goes as missionaries to the pagan Gaelic inhabitants. In addition to teaching me about the geography, zoology and history of these Britons, the book reflects on what it means to be a missionary—to inhabit a particular place, to love and mingle with others, to find God already there even in the most remote places.

England’s Lane by Joseph Connolly, Quercus, 2012, 532 pp.

I picked up this book because it’s set in our neighborhood in London. England’s Lane is just at the end of our street, and we venture there almost daily for coffee or groceries. This novel tells about life in the 1950’s, with three couples living and working there—the ironmonger, the confectioner and the butcher. The story taught me a lot about our neighborhood and about post-war London, and the writing was excellent. However, it was a novel driven by character development rather than plot, and I didn’t find any of the characters particularly likeable. That made it feel like a bit of a slog at times, but that may also have been the timing. I started it in January, and slowly finished after my father’s death in February.

Girl Reading by Katie Ward, Virago, 2012, 352 pp. (Not Pictured)

This novel was almost like a series of short stories, moving through time. In each, a girl or woman’s story unfolds around the time an artist captures her image, and in each of those images, she is (or appears to be) reading a book. The book was exquisitely crafted, and each of the stories made me want an entire novel about those characters. I enjoyed moving through the ages (stories move chronologically from the 14th century to the future 21st), even as I wanted to linger with each set of characters just a bit longer. Definitely recommended!

JUST FOR FUN

These last books were just for entertainment. They were good and well-written, but not outstanding or especially memorable. (I am struggling to recall the details of some enough to even write these small reviews.) We all need that kind of fiction in our lives as much as the profound and life-changing kind.

The Trouble with Goats and Sheep by Joanna Cannon, The Borough Press, 2016, 454 pp.

The Trouble with Goats and Sheep by Joanna Cannon, The Borough Press, 2016, 454 pp.

This is the story of a British neighborhood in the 1970s. Mrs. Creasy has gone missing, and two ten-year-old girls decide to take on the job of finding out what happened. It opens them to adult realities and to the complicated relationships within households and between neighbors. As someone who was just a little younger than the characters in the 1970s and is the mother of a ten-year-old, I connected with the story in several ways. I also enjoyed understanding all the Britishisms in the book, which I never would have gotten before!

The Muse by Jessie Burton, Picador 2016, 445 pp.

I enjoyed this book because it introduced me to worlds I would never otherwise see—London art galleries in the late 1960s and Spain in the Spanish Civil War. The story was about a painting created in 1936 Spain, discovered by a young gallery worker in the 1960s. The characters were likeable, and the plot was interesting, as we come to discover the painting’s origins alongside them. A fun and fast read.

The Innocents by Francesca Segal, Vintage Books, 2012, 436 pp.

This book is also set in North London where we live, but much wider ranging than one little street. It’s a story of love and family, set in the tight-knit Jewish community here. Adam and Rachel are childhood sweethearts, but Adam has feelings for her wild cousin Ellie. The book follows Adam as he feels torn between Rachel and Ellie. I loved the way the story lifted up the tangled relationships between family, community, faith community and more as he considered the possible consequences of his choices. Another entertaining and enjoyable read.

The Carriage House by Louisa Hall, Penguin Books, 2013, 279 pp.

This story struck me as one about upper class fears of decline. William Adair is a wealthy man with three daughters, for whom he had enormous dreams—and who have each stumbled along into disappointment. When he has a stroke, they return to care for him and fight to preserve the beloved Carriage House behind their home. In so doing, they are able to shake off the shadow of his expectations find themselves and even discover a bit of joy. Good to pass an afternoon or two, but not especially memorable.

Creating Congregations of Generous People by Michael Durall, Alban Institute, 1999, 104 pp.

I’ve been reading a lot of book about stewardship lately, as my congregation is struggling to learn and grow in this area. Michael Durall’s book was cited by several others as an important resource. It is no longer in print, but I found a copy easily at half.com for less than a dollar.

I’ve been reading a lot of book about stewardship lately, as my congregation is struggling to learn and grow in this area. Michael Durall’s book was cited by several others as an important resource. It is no longer in print, but I found a copy easily at half.com for less than a dollar.

I was surprised by the tone of this book, from the beginning. Most stewardship experts write in a way that is frank, but relentlessly encouraging. They seem to say, “You’re doing it wrong, but if you do these things, you’ll be rich!” Durall has all the frankness, but a much less cheery outlook–while maintaining that congregations can create generous people and provide ample resources for their ministry.

First, Durall acknowledges that most people give the same amount, year after year, without significant increase. He argues that traditional pledge drive methods (especially those that emphasize the annual budget) actually encourage and reinforce low-level and same-level giving patterns. Durall names the 80/20 rule–that 20% of the people carry 80% of the load of work and giving. What makes his work different, though, is that he argues that increasing stewardship is not about going after the 80%, but increasing the 20%. He says that most people in the bottom 80% do not know why they give the way they do, resist changing it, and that “attempts to increase the giving level of the bottom 80% of the congregation may be futile.”

Durall backs this up with experience and research. He counters the dictum that “money follows mission,” common in so much of the literature, including the popular J. Clif Christopher books.

Increased programming (expanding the mission) will not motivate 80% of the members of most congregations. … Parishioners who give the least are motivated by maintaining the building and the congregation. More generous parishioners believe they are also helping people who are less fortunate, and strengthening their relationship to God. (26-27)

He names the deep intransigence of a church’s giving culture, and the sustained effort required to transform it. While he does agree that people should be encouraged to give to God and not to church, that we need to be emphasizing mission, he does not think this is enough to overcome longstanding patterns of same-level and low-level giving.

Durall instead invites us to nurture the trait and spiritual discipline of generosity throughout our churches.

Charitable giving should make some difference in how we as religious people experience life from day to day. If giving to your congregation is similar to writing a check at the end of the month to pay the phone bill or the electric bill, and then forgetting about it until the end of next month, you are not giving enough. Similarly, if you take spare change or a dollar or two from your pocket or purse for the weekly collection and never notice the difference, your giving has too little meaning either for you or for your church. (38)

The remaining chapters offer some practical advice and exercises, some of which are familiar (like not encouraging giving to the budget) and some of which were new to me. I found his advice to ministers especially helpful. While he agrees with J. Clif Christopher that ministers should know what people give, Durall assumes they probably will not, and that makes his guidance most helpful. He says that the minister should “introduce the importance of stewardship to the congregation at the earliest opportunity,” which is best accomplished by making a leadership gift and sharing that intent with the church, even before a call is issued. (49) I love this idea. He adds to the minister’s list: stressing the importance of giving to new members, encouraging a mentality of abundance over scarcity, setting vision and clarifying roles, and including stewardship in worship regularly–especially by finding ways to thank people.

Durall’s concrete advice about stewardship builds upon his realistic assessment of congregational giving culture, his claim that we are to be building generous people, and a commitment to year-round stewardship. Though it is older, Durall’s book offered new ideas and perspectives that I have already shared with my Stewardship Team and we are finding ways to use in our congregation. Some might find his less-than-optimistic read on giving cultures depressing, but I found it honest and helpful. I think this is a worthwhile addition to every pastor’s stewardship library.

Book Review: Abide With Me

Posted on: March 25, 2014

Abide With Me by Elizabeth Strout, Random House, 2006, 294 pp.

Oh, what a beautiful novel this is. It is a profound testimony to grief, community, ministry and the relationship between a church and its pastor. I need novels for myself, for my own emotional well-being. Sometimes, I have a tough time breaking down and working through my own feelings. The problems are too close and too complex and they feel overwhelming. A good novel lets me do the emotional work a bit vicariously–weeping, grieving, sitting in silence. Abide With Me was just that kind of book.

Oh, what a beautiful novel this is. It is a profound testimony to grief, community, ministry and the relationship between a church and its pastor. I need novels for myself, for my own emotional well-being. Sometimes, I have a tough time breaking down and working through my own feelings. The problems are too close and too complex and they feel overwhelming. A good novel lets me do the emotional work a bit vicariously–weeping, grieving, sitting in silence. Abide With Me was just that kind of book.

The novel tells the story of Rev. Tyler Caskey, a pastor to a small town church in Maine. It is the story of his marriage to an unlikely candidate to be a pastor’s wife, of their love and their struggles and her untimely death. It is the story of his daughter Katherine, age 5, and how his grief and her own break down in her life. It is the story of the members of the parish–the organist who wants a new organ and her husband reckoning with his unfaithfulness; the housekeeper who befriends him in spite of her shady past; the teacher and school psychologist who play out their own assumptions on him and his daughter, on and on. It is a story about the heavy, heart-wrenching work of grief, the toll it takes on a life to engage that work, and the even greater cost of ignoring it. In the end, it is a story of redemption and the power of community to move beyond rumor and gossip into love. It is a story of imperfection and vulnerability between pastor and congregation, told with hope and affection.

Strout includes many insightful gems from the life and mind of the minister, like Tyler’s desire for “The Feeling,” the “profound and irreducible knowledge that God was right there” (15) and his reflections and comparisons of his own calling with that of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, which many a pastor has done (including this one). At one point, his sister accuses him of caring too much about the feelings of others: “If you’re always thinking of the other person first, you don’t have to bother with what you’re feeling. Or thinking.” (123)

When Tyler’s grief finally overtakes him and he breaks down in the pulpit, the organist subtly begins playing “Abide With Me,” his favorite hymn, while the head deacon comes forward and takes his hand. His seminary professor then tells him,

Your congregation, it seems to me, has given you love. And it’s your job to receive it. Perhaps before now they gave you an admiring, childlike kind of love, but what happened to you that Sunday–and their response to it–is a mature and compassionate love. (286)

I am blessed to serve that kind of congregation, and I was blessed to read about Tyler Caskey’s congregation, the way they cared for each other as pastor and congregation. Thank you, Elizabeth Strout, for Abide with Me.

Book Review: Mudhouse Sabbath

Posted on: January 24, 2012

Mudhouse Sabbath: An Invitation to a Life of Spiritual Discipline by Lauren F. Winner, Paraclete Press, 2003, 161 pp.

Last week, a high school friend who I had not seen in nearly 20 years contacted me on Facebook to let me know he was passing through my town, and invited me out for coffee. It was a delight to catch up, and the conversation flowed free and easy even after so many years. For me, it was a special treat to talk to someone who knew me before marriage, motherhood and pastoral life—as if he could unlock a more primitive version of myself, one that I have already unearthed a bit during this sabbatical time.

Last week, a high school friend who I had not seen in nearly 20 years contacted me on Facebook to let me know he was passing through my town, and invited me out for coffee. It was a delight to catch up, and the conversation flowed free and easy even after so many years. For me, it was a special treat to talk to someone who knew me before marriage, motherhood and pastoral life—as if he could unlock a more primitive version of myself, one that I have already unearthed a bit during this sabbatical time.

As it always seems to with me, conversation turned toward the realm of the spiritual and the religious. (I realized in this reunion that this sort of thing always happened way back in high school too, not just with him but with all my friends. I guess my calling was inevitable.) My friend described himself just like he did in high school—not a believer, but someone with a deep fascination and appreciation for the spiritual realm and the mythos of religion. He expressed a sentiment like, “I wish I could believe, but no one has been able to show me more than the man behind the curtain.” At the time I responded somewhat pathetically with a torrent about liberal Christianity, welcoming doubts, honoring questions and joining as Jesus-followers even if we weren’t sure what we believed.

What I really should have said, and what I am coming to believe ever more deeply, is the premise of Mudhouse Sabbath: that religious life (aka spiritual life) is not about belief, it’s about practice. Following a religious tradition is not about conforming your mind, it is about cultivating a way of life. Religious life is about taking on habits of living that have led seekers to God and transformed wayward souls into faithful followers for millenia. Whether we believe or do not believe, whether we “feel it” or not, religious practitioners continue to follow these ways of life—not because we have a blind allegiance to tradition, but because the practice of spiritual discipline shapes us in ways that make belief possible and mystical experiences knowable.

Lauren F. Winner’s Mudhouse Sabbath is a unique approach to this ongoing conversation about practices of faith. Winner was raised in an observant Jewish household, but converted to Christianity as an adult. She loves her Episcopalian church life, but misses the disciplines of her Jewish roots. This book, then, takes a look at a host of Jewish spiritual disciplines, compares Jewish and Christian practices, and imagines how Jewish ideas and habits might shape a Christian spiritual life as well.

It is important to note that Winner begins the book by refuting my claim about belief versus practice.

Action sits at the center of Judaism. Practice is to Judaism what belief is to Christianity… for Jews, the essence of the thing is a doing, an action. Your faith might come and go, but your practice ought not waver. (ix)

For Christians, however:

Spiritual practices don’t justify us. They don’t save us. Rather, they refine our Christianity; they make the inheritance Christ gives us on the cross more fully our own. … Practicing the disciplines does not make us Christians. Instead, the practicing teaches us what it means to live as Christians. … The ancient disciplines form us to respond to God, over and over always, in gratitude, in obedience, and in faith. (xii-xiii)

I am no longer convinced of Winner’s claim that the practices do not make us Christians. I do agree that our spiritual practices do not justify us—God’s grace does that. However, I question how we can call someone a Christian when they believe all orthodox doctrine, but do not let it influence their life decisions in any way by practicing love, generosity, prayer and compassion. The same is true in reverse: if you follow Jesus as the shaping influence of your life through acts of love, generosity, prayer, compassion and worship, but you are not sure what you believe, I think you are still a Christian. In this light, I doubt Winner would disagree, but it is something I continue to wrestle with, as someone whose life often has more doubt, more practice, and less confident belief.

None of that is the heart of the book, however. Winner’s book is primarily a description of the Jewish spiritual disciplines, a comparison to Christianity, and an invitation to Christians to make these practices a part of our lives. She describes eleven different practices: Sabbath, fitting food (keeping kosher), mourning, hospitality, prayer, body, fasting, aging, candle-lighting, weddings and doorposts (hanging mezuzot on doorposts).

What drew me to her book was what has always drawn me to Jewish spirituality—its embodiedness. So many traditional Christian spiritual disciplines (prayer, meditation, lectio divina, silence) focus on the mind and spirit. The practices Winner describes are much more physical—stopping work on Shabbat, caring about the kinds of food we eat and how they are prepared, placing physical markers in our homes and on our bodies to remind us of our faith. I have always been cautious about adapting any of these practices as my own, since I am not grounded in the community that shapes them. Winner has opened the door for me to imagine ways to incorporate these kinds of practices into my Christian life, with an appreciation for their Jewish origin and not a presumptuous attempt to imitate Judaism. I wrote recently about the spirituality of housework, which works for me in the same way as the practices Winner describes and reminds me of the Shabbat preparations she discusses.

This is a great introduction to spiritual disciplines that is accessible to everyone. It is a short book that would make a great subject for a church book discussion group or Sunday school class. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Leadership for Vital Congregations, by Anthony B. Robinson, Pilgrim Press, 2006, 128 pp.

This is a book I wish I had found and read a long time ago–even before 2006, when it was first published. Over the last five years, I have been engaged in leading a church through a time of major change. I found Robinson’s book Transforming Congregational Culture incredibly helpful in understanding the kind of change required, and his book with Robert W. Wall, Called to Be Church: The Book of Acts for a New Day shaped a sermon series I preached to help my congregation understand and tackle these issues from a biblical framework. This book on leadership brought together much of what I have learned over the past five years of this journey, and encapsulated it in a clear, straightforward way. Having read Robinson’s earlier books and many of the books he cites as references, I felt familiar with most of the guidance he offers, but I have never seen anyone collect and share it so directly and concisely.

This is a book I wish I had found and read a long time ago–even before 2006, when it was first published. Over the last five years, I have been engaged in leading a church through a time of major change. I found Robinson’s book Transforming Congregational Culture incredibly helpful in understanding the kind of change required, and his book with Robert W. Wall, Called to Be Church: The Book of Acts for a New Day shaped a sermon series I preached to help my congregation understand and tackle these issues from a biblical framework. This book on leadership brought together much of what I have learned over the past five years of this journey, and encapsulated it in a clear, straightforward way. Having read Robinson’s earlier books and many of the books he cites as references, I felt familiar with most of the guidance he offers, but I have never seen anyone collect and share it so directly and concisely.

Robinson begins by describing various images of leadership, in an attempt to expand our images of leaders and their tasks. Influenced by Ron Heifetz, he describes the task of leaders as “mobilizing a group or community to make progress on its own toughest challenges and problems.” (24) He points out some factors unique to pastoral leadership, such as working with volunteers, being more accessible than most leaders, and understanding God’s leadership as ultimate. One chapter is a very helpful literature review of some of the most widely respected secular writers on leadership. This was an excellent introduction to these authors, but also serves to broaden the imagination about the function and purpose of leadership.

Robinson’s chapter entitled, “Pastoral Leadership: Seven Strategies,” is what really made me wish I’d had this book several years ago. He describes seven leadership strategies that pastors must follow in order to lead. They are sequential—you must do one before the other—but pastoral leaders are always doing all of these steps as they move ahead in leading congregations. Everything starts with building trust (Strategy One), and discerning what’s going on (Strategy Two), why we are here (Strategy Three) and what God is calling us to do (Strategy Four). Once change begins, the pastoral leader manages distress (Strategy Five), persists (Strategy Six) and helps build a learning congregation (Strategy Seven). This is exactly what we have been doing in our congregation over the last five years. It is almost an exact map of the terrain we have covered in our change process. I only wish I’d had the map ahead of time—it would have made me feel less like a wilderness wanderer!

The remaining chapters talk about sustainability practices in leadership. Robinson talks about growing and developing spiritual leaders, the role and responsibilities of the congregation, caring for your soul as a leader, and leadership itself as a spiritual practice. I have never heard anyone talk about leadership itself as a spiritual practice, and I found myself saying, “yes! yes! yes!” He outlines five specific examples drawn from the story of Moses about how leadership is a spiritual discipline, but I thought of a dozen more. For me, the act of prayer and discernment with God about my congregation and how I am called to challenge and connect with them is incredibly holy. It has made me a better Christian and a better person. The act of leading a congregation engages my heart and soul for God’s use just like personal prayer, study, meditation or sabbath-keeping. It shapes me in the ways of Christ. For example, our church is currently engaged in a capital campaign. Being a pastoral leader challenging others to greater generosity has transformed me into a more generous person. It was a gift and a revelation in this book for Robinson to name that as a spiritual discipline.

This book is an excellent starting point for anyone interested in engaging in deep, transformative work as a pastoral leader. In a few short pages, Robinson summarizes what that kind of leadership looks like, the basics of how to do it, what to expect and how to sustain it. This book will not tell you the details of why the church needs to change (see Transforming Congregational Culture for a good primer on that one), how to conduct a visioning or planning process, what changes the church should be making, or even what your changed church should look like. There are plenty of other books out there that will do that. Instead, Leadership for Vital Congregations tells you what kind of leader you need to be to get there. If you want to be that kind of transformational leader but don’t know how to start, start here. Like any map, this book won’t tell you where you need to go or describe the details of the landscape you’ll see. It will simply orient you on the journey. You’ll have to trust God, your congregation and your own discernment for the rest.

Somebody Else’s Daughter, by Elizabeth Brundage, Plume Books, 2008, 342 pp.

At long last, after holidays and funerals and ministry galore, a chance to read! I picked up this book back in November from the clearance table, hoping for a little light diversion over the Thanksgiving weekend. I finally started it on MLK Day, and discovered it was a great choice.

At long last, after holidays and funerals and ministry galore, a chance to read! I picked up this book back in November from the clearance table, hoping for a little light diversion over the Thanksgiving weekend. I finally started it on MLK Day, and discovered it was a great choice.

Somebody Else’s Daughter has a great cast of multi-generational characters, centered on an elite prep school in the Berkshires. The middle-aged generation of characters is comprised of the headmaster and his wife, a teacher, and several wealthy parents. The student generation of characters are the daughter of the headmaster, a local prostitute, the child of a single mother who moved to the school after a very different life, and the adopted daughter of two wealthy parents, who is also the birth daughter of the teacher. Everyone in the book has a past full of secrets, and the story uncovers them one by one.

Brundage wove this story together in a beautiful way. The story draws you in like a spider in a web. I had no idea where it was going, what the plot was going to be, but it didn’t matter. I was captivated by each of the characters and by Brundage’s simple yet exquisite writing. Each chapter, each scene stood on its own, yet there was mystery after mystery unfolding. As it rolled along, I started to pick up clues about upcoming plot twists, but they were subtle and indirect. Then, almost suddenly, I looked up to find myself in the middle of a mystery and a thriller for the final hundred pages or so.

The experience of reading this novel reminded me of riding the log flume. Most of the ride is a gentle, rolling trip through the trees and around some corners. Then, you enter the old wooden sawmill, see the giant spinning blade and your heart starts to beat a little faster. At the end, you go crashing down below the blade, now the incline at top speed into a big splash, laughing with delight. Somebody Else’s Daughter was a great ride, and just the escape reading I needed.

Book Review: Almost Christian

Posted on: December 18, 2010

Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers is Telling the American Church, by Kenda Creasy Dean, Oxford University Press, 2010, 254 pp.

This book seriously knocked my socks off. I was expecting a sociological look at youth ministry based on the National Study of Youth and Religion, filled with statistics about how our youth are falling away and the church is threatened with greater decline. I also expected some of the traditional suggestions about revamping our church style to attract the next generation. This book was none of those things. Instead, what Kenda Creasy Dean offers here is a prophetic indictment of American Christianity, based on the perspectives of our young people and solidly grounded in theology and biblical perspective. I read it once, and anticipate reading it again.

This book seriously knocked my socks off. I was expecting a sociological look at youth ministry based on the National Study of Youth and Religion, filled with statistics about how our youth are falling away and the church is threatened with greater decline. I also expected some of the traditional suggestions about revamping our church style to attract the next generation. This book was none of those things. Instead, what Kenda Creasy Dean offers here is a prophetic indictment of American Christianity, based on the perspectives of our young people and solidly grounded in theology and biblical perspective. I read it once, and anticipate reading it again.

The core of the book centers on an interpretation of the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), which was a massive research study from 2003-2005 into the spiritual and religious lives of youth, including surveys and extensive interviews of young people across the United States. The book Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers published the initial results and introduced the concept of “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” as the true faith practice of most teens. Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is a pseudo-religious belief system that emphasizes being good and nice, feeling happy and good about oneself. The God of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism created the world and watches over it and helps out when we have problems, but is otherwise uninvolved in our lives and makes no demands of us other than being good, nice and fair. Soul Searching talked about Moralistic Therapeutic Deism as a displacing substantive religious faith with “personal happiness and interpersonal niceness.” (Almost Christian, 14)

Kenda Creasy Dean does not take issue with the research of Soul Searching, since she herself was a researcher in the NYSR. What she does, however, is shift the burden (and blame) away from youth and squarely on to the shoulders of the church, parents and the example we have set. She argues that, in the interest of making Christianity appealing, we have failed to make it anything of consequence. Youth in the study generally have positive feelings about religion, because they don’t think it matters very much. We have not shown them, by the example of our lives and the missional imagination of our churches, that Christian faith makes any difference at all.

I have seen Moralistic Therapeutic Deism at work in the lives of the youth in my congregation, and I have struggled to break through it in my conversations with them. I also recognize my complicity in the problem. I have shied away from the hard truths of sin and sacrifice in an attempt to make Christianity appeal to young people. I have downplayed the reality that the God of Jesus Christ demands we give up everything to follow, that we take up our cross and abandon our possessions, in fear that such a high price might scare them away altogether.

The good news is that it’s not too late, and the church already has everything needed to invite our young people into consequential faith. Dean names the arts of “translation, testimony and detachment”–practices that help us understand our story as part of God’s story, that help us articulate our faith for others to hear, and help us let go of the things of this world and see with God’s perspective. The way to teach people that kind of faith is by example—the example of parents and church members living lives of sacrifice and service in God’s name, sharing their faith with the next generation.

Anyone who cares about youth and youth ministry should read this book. So should anyone who cares about the future and the vitality of the church. There is much more substance and sophistication than I can convey in this short review. It is a rich and compelling read. Dean’s convincing argument is that the faith of our teenagers is the faith of their parents, and the faith the church has been teaching. We all find ourselves co-opted by the power of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. The power of this book is the depth of analysis Dean offers, steeped in theological, biblical and spiritual insight. Like all good prophets, she offers a scathing conviction, and then she tells us how God is going to redeem us and sets us on the path toward righteousness.